Archaeology and the beyond in tropical paradise

To Associate Professor Julie Field, the Pacific islands are more than just places for luxurious, tropical getaways — they’re her laboratories.

Existing in relative isolation, islands provide the perfect conditions for archaeologists to pinpoint exactly when people arrived and what changes they brought with them. Field is specifically interested in the evolutionary relationship between humans and the environment — a curiosity that has taken her to the Hawaiian and Fiji Islands and back for nearly 25 years.

“Human beings do things like cut down the forest, introduce plants or kill all the native birds whose waste contributed to the chemistry of the soil,” Field said. “There is a dramatic shift where human beings and the environment change together, and that’s what I study.”

In Fiji, her research focuses on the emergence of agriculture in prehistoric societies from about 2,500 years ago. By questioning how people made farming decisions based on dietary needs, environmental conditions and available resources, Field is illuminating larger ecological and evolutionary trends driven by humans. Her work in Hawaii surrounds similar questions in relation to societies existing roughly 1,000 years ago, which were often in competition with one another for land for crop and fish farming.

Through archaeological excavation, isotopic analysis, GIS modeling and speaking with indigenous communities, Field observes patterns in fire history, the use and introduction of plants, fossils from wildlife and livestock, soil chemistry and more.

“How do people develop in tandem with the environment? How do we move as groups into different kinds of living?” Field said. “As our population grows and we’re more and more reliant on just a few sources of food, we need to have some kind of understanding of how the transition to agriculture actually played out in different places of the world so we can make decisions moving forward.”

The geographical and biological similarities of Fiji and Hawaii allow Field to compare her data from the two regions, slowly painting a picture of how human societies form, move and alter their behavior in relation to various environmental factors.

Follow Professor Field on Instagram >>

In Hawaii, her data suggest some communities had knowledge about how to keep ecological systems in balance.

“They were able to collect and consume plants and animals, but they would target species that were resilient and produced at a faster rate so that there wasn’t as big of an impact,” said Field, adding that her research also documents cases where humans have produced less favorable environmental trajectories.

“If there’s too much burning of a landscape, like in Fiji, where there’s a long history of burning, eventually the organic system in the upper layer of the soil is burnt out, and then erosion happens,” Field explained. “That’s a cautionary tale for how fire should be used to manage landscapes and how the frequency of fire plays into ecological resilience.”

In her teaching, Field said she aspires to instill in her students an appreciation of how archaeology can have implications for modern people and ecological concerns.

This summer, she’s working with three graduate students on two projects in Fiji and one in Samoa.

In Fiji, PhD student Kyle Riordan will study an ancient trail system that ecotourist companies want to start allowing backpackers on. In addition to traditional archaeologic methods, Riordan will also speak with native communities about the trails’ history and importance.

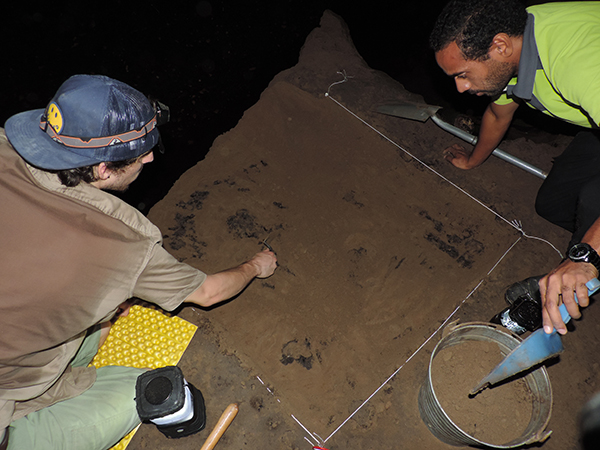

PhD student Kyle Riordan (left) works at Naihehe Cave in Fiji

First-year master’s student Samantha Kirgesener will compare prehistoric mollusk fossils, found during Field’s excavations on the islands, with modern-day mollusks sold in local Fiji markets to see how foraging pressures have impacted the size of the animals over time. These analyses can have real-world implications for size limits in modern fisheries.

In addition to the knowledge and guidance Field brings her students as a research advisor, she also cares about them as people.

“Dr. Field is an outstanding advisor and mentor,” said second-year master’s student Craig Shapiro. “Whether it is writing us holiday cards, bringing us souvenirs from her trips away from Columbus, asking about our well-being or inviting us to share meals at her home with her family, she often finds ways to show that she cares about her advisees.”

This summer, Field will accompany Shapiro to Samoa, where the team will examine prehistoric agricultural features such as ditches and terraces, which can provide details about the transformation of forested landscapes into those for open farming.

“Because of [Field], I know my decision to choose Ohio State was the right one,” Shapiro said.

Field said she hopes to train her students to not only engage in high-quality research, but to become integrated in the communities they work in and be able to communicate about the relevance of archaeology to common needs and goals in the present day.

“We have turned our planet into almost like a factory, or a really big farm, and we use that to support ourselves and our growing human population,” Field said. “The problem with that is we don’t necessarily have any provisions for preserving all of the wild spaces or the creatures that are in them, which are really the engine for change."

"We as archaeologists have all this information about what animal and plant life was in the past, and all of that can be applied to how we are going to manage those resources in the future.”

Original story on Arts and Sciences page